The Separate Car Act: A 19th Century Civil Rights Case Worth Revisiting

By Alexander P. McBride, Senior Counsel

What did the ins and outs of the 19th-century U.S. Supreme Court decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, the rationale for Jim Crow racial segregation laws, teach us?

Homer Plessy was seven-eighths White and one-eighth Black — pejoratively referred to as an “octoroon” in the 19th century. Plessy came of age during the age of Reconstruction in New Orleans, when people of color were granted expanded civic and political rights. After the withdrawal of federal troops from the South in the late 1870s, however, Louisiana swiftly passed and enforced “Jim Crow” discriminatory laws against anyone less than “pure” White, including “octoroons” like Plessy.

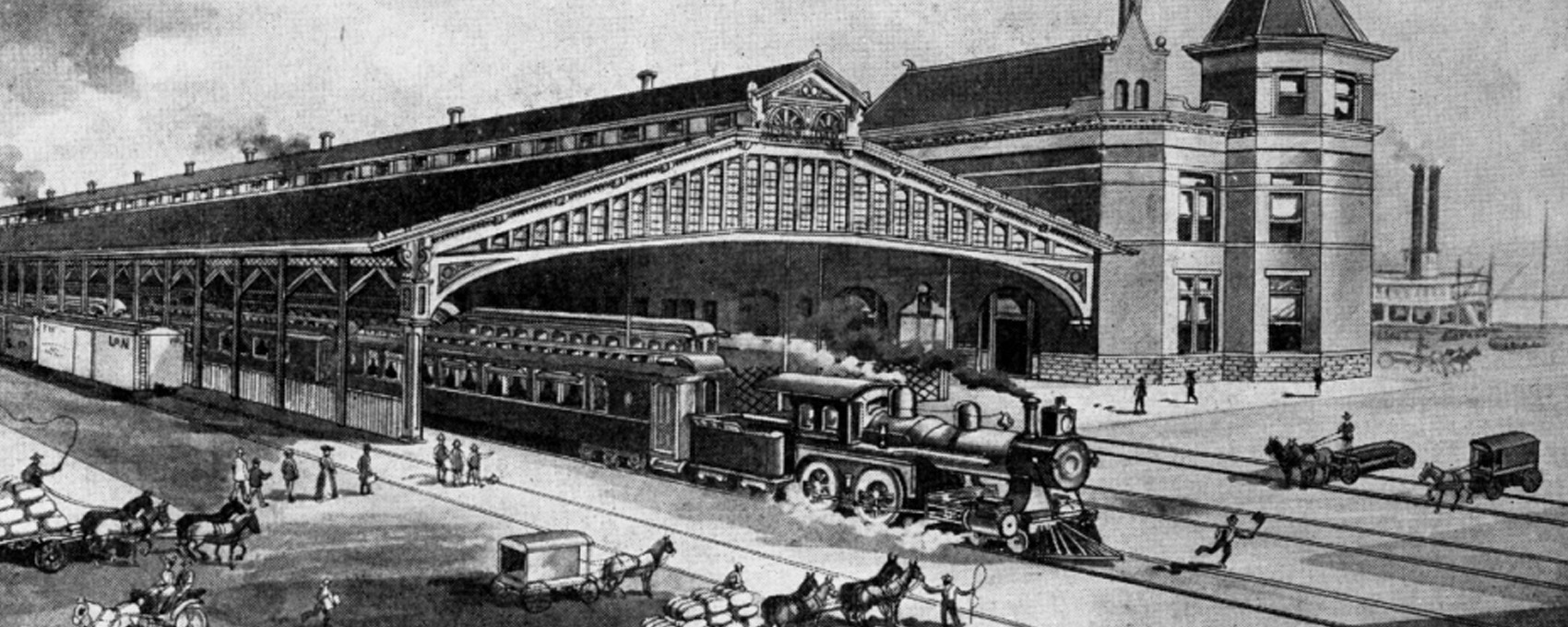

Accordingly, in 1890, Louisiana passed the Separate Car Act, which required “separate railway carriages for the [W]hite and colored races.” The act required that all passenger railways provide separate cars for Blacks and Whites, stipulated that the cars be “equal” in facilities, banned Whites from sitting in Black cars and Blacks in White cars (with exception to “nurses attending children of the other race”), and penalized passengers or railway employees for violating its terms.

In 1892, a 30-year-old Plessy was recruited by an eclectic New Orleans civil rights group known as the Comité des Citoyens to challenge the “Separate Car Act” in a planned test case. Plessy agreed. Thus, on June 7, 1892, Plessy purchased a first-class train ticket for a trip between New Orleans and Covington, Louisiana, taking a vacant seat in a “Whites”-only car. As required pursuant to the Separate Car Act, a conductor then asked Plessy if he was a “colored man.” Plessy answered in the affirmative and was swiftly ordered to the “colored” car. Plessy refused. The conductor halted the train before it left New Orleans, and the police arrested Plessy and threw him in jail.

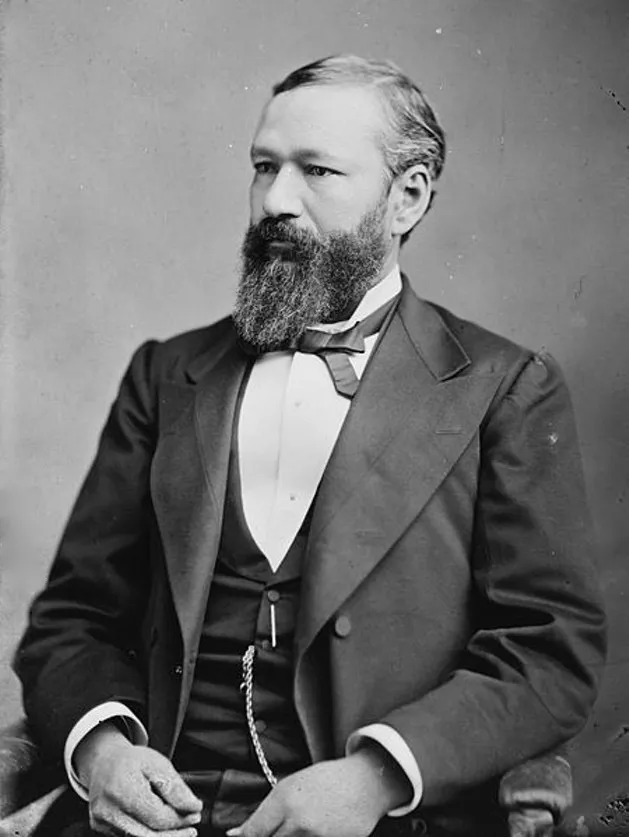

Plessy was brought to trial in New Orleans before Judge John H. Ferguson and convicted of violating the Separate Car Act. Judge Ferguson denied Plessy’s petition to throw out the case. Plessy then appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court, arguing that the law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which forbids states from denying “to any person within their jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” as well as the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which banned slavery. The Louisiana Supreme Court affirmed Plessy’s conviction. Plessy then appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, again challenging the constitutionality of the Separate Car Act.

Supreme Court Plessy Decision

In a 7-1 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Separate Car Act was Constitutional. The Supreme Court reasoned that, while the purpose of the 14th Amendment was to create “absolute equality of the two races before the law,” such equality extended only so far as political and civil rights (e.g., voting and serving on juries), not “social rights” (e.g., sitting in a railway car one chooses). As Justice Henry Brown’s opinion put it, “if one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” Furthermore, the Supreme Court held that the 13th Amendment applied only to the imposition of slavery itself, not to a right to equal facilities.

The Supreme Court expressly rejected Plessy’s arguments that the law stigmatized Blacks “with a badge of inferiority” in violation of the Constitution — pointing out that both Blacks and Whites were given equal facilities under the law and were equally punished for violating the law. The racial segregation itself was simply a product of the state’s legitimate “police power” to keep good order.

In the end, held the Supreme Court, the only “stigma” or “discrimination” resulting from the Separate Car Act was in the mind of Plessy himself. Employing a kind of victim-blaming logic, Justice Brown held,

“We consider the underlying fallacy of [Plessy’s] argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan entered a powerful, lone dissent. While agreeing that the “[W]hite race” was the “dominant race” “in prestige, in achievement, in education, in wealth, and in power,” Justice Harlan argued this claimed “superiority” had no standing under the Constitution:

“In view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.”

Brown v. Board of Education

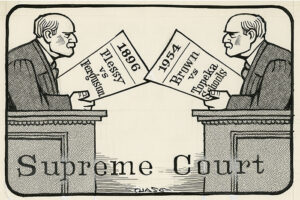

Until the mid-20th century, Plessy v. Ferguson gave the official, “Constitutional nod” to the “separate but equal” doctrine that condoned racial segregation in public places, foreclosing legal challenges against increasingly segregated institutions throughout the South.

Then, in the landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the “separate but equal” doctrine was abruptly overturned when a unanimous Supreme Court ruled that segregating children by race in public schools was “inherently unequal” and violated the 14th Amendment — directly rebutting the Plessy Court’s holding that the “stigma” created by racial segregation was not forbidden under the Constitution.

Yet, notwithstanding Brown, the Southern United States remained racially segregated well into the 1960s, even though the Supreme Court consistently ruled racial segregation in public settings to be unconstitutional. For example, in Heart of Atlanta Motel Inc. v. United States (1964), the Supreme Court officially held racial segregation in places of public accommodations was unconstitutional, even though such ruling was (at least) implied 10 years earlier in the Brown decision.

The back of racial segregation was finally broken by federal statute pursuant to the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Plessy Pardoned

Plessy died in 1925. It would have been impossible even in the 1920s for Plessy to recognize his extraordinary place in history, when racial segregation seemed inviolate, racial lynching throughout the United States was rampant, and the Ku Klux Klan was at its peak, with millions of members throughout the country and major marches on Washington. Yet within just a few decades came the Civil Rights Revolution, and Plessy gained new historic life. In January 2022, Louisiana Gov. Bel Edwards posthumously pardoned Plessy for his conviction under the Separate Car Act, formally vindicating Plessy 130 years after his original challenge.

About the Author

Alexander P. McBride is a seasoned commercial litigator who has prosecuted and defended a multitude of complex commercial actions from inception to appeal. He spent nearly a decade at a top-tier Am Law 100 global law firm, where he defended numerous high-profile securities and structured finance litigations, SEC and DOJ investigations, congressional inquiries, and Chapter 11 adversary proceedings. Mr. McBride also served as national counsel for a major corporate trustee advising on business risk and strategy and has represented investors and trustees in interpleaders and other complex indenture disputes.